|

<< continued from page 1

Despite—or perhaps because of—this idea of "Englishness", Shakespeare's Tempest has been the source of enormous cultural debate, adaptation, and reinterpretation in the last one hundred years. With massive decolonization across the world in the first part of the twentieth-century, the slave Caliban became the focal point of postcolonial intellectuals calling for the de-privileging of the Prospero colonizer. Writers such as Aime Cesaire and Ernest Renan, as well as social scientists such as Mannoni, clung to Caliban-the-concept in their negotiation of postcolonial identities. For most postcolonial writers, this meant placing Caliban center-stage, re-writing or adapting The Tempest so as to make this lost voice central.

Within this context, Tara's interpretation of Shakespeare's Tempest takes on new cultural significance. Tara's production is significant not only because of its Asian-British cast, but also because of its clear decision not to adhere to the body of work that preceded it—a decision which has baffled some. Verma recalls a press conference in which, "an outraged academic asked why my company was producing Shakespeare at all—and if we were, why could we not 'do it straight'? Another wondered whether we were going to 'Bollywood-ise' it, complete with cod-Indian accents." Eschewing the cod-Indian accents and Bollywood pyrotechnics, Verma has put together a production that also distances itself from a Shakespearean trend in which Prospero as a symbol of the former colonizer (i.e. Britain) must come to terms with the gradual loss of his power.

Indeed, no description could be further from the Prospero with whom audiences are presented on the stage at the Arts Theatre. Robert Mountford's Prospero, far from facing a loss of control, is described by Philip Fisher in his review as "a sadistic, hectoring control freak, who rules the island and its inhabitants with an iron fist."[9] Prospero's presence on the stage is commanding and, as Fisher suggests, his speeches take on new resonance when they become the words of a commanding, controlling and vengeful Muslim man. In his notes on the performance, Verma references Ayman al-Zawahiri and Said Imam al-Sharif, members or former members of Al-Qaeda, as inspirations for the character of Prospero. It is the ethnic dimension of this performance and its implicit reference to the threat of Islamic terrorism that most explicitly separates Tara's production from its postcolonial predecessors. The motifs of imperialism so frequently called upon in contemporary productions of The Tempest cannot help but be complicated in the pairing of a Middle Eastern Prospero and an African Caliban. In this sense, it is truly a 21st- rather than 20th-century performance, taking into account shifts of power in a post-postcolonial world.

To place Prospero in the hands of an actor foreign to ingrained conceptions of Shakespeare and Englishness—as well as the tropes of postcolonial theory—is perhaps far more subversive than rewriting Shakespeare's text in order to place Caliban at its center. What Tara presents us with is a reconception of the world in which the cultural power of Shakespeare qua Prospero lies not in purity or authenticity but in a 21st Century hybridized English identity.

Mountford's Prospero has special resonance in London, not only in the wake of the 7/7 suicide bomber attacks, but also in a body of cultural work that has sought to reevaluate English national identity. Over the past few years there has been an enormous interest in the history of English nationalism (hitherto disregarded as nonexistent)[10] and in the possibilities for expansion of that identity to include the enormously international population now living in England and London in particular. This change in sensibility is in part the product of the rise of postcolonial studies and the development of concepts of hybridity and nationalism. The call today is for a Britain that is able to validate a much broader definition of what it means to share in English heritage and identity than was previously possibly. Verma's project, supported by intellectuals such as Hanif Kureishi and Salman Rushdie, is a part of this project to redefine British national identity. In Tara's Tempest we are asked to accept Mountford as a Shakespearean player and a Muslim, and also to see the production as reflective of 21st Century Britain's ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity.

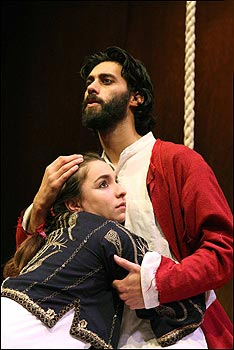

The plea for affirmation of the Englishness of Verma's actors is clearly seen not only in their impeccable English accents, but also in the character doubling, a theatrical device that emphasizes the continuity between characters otherwise unassociated. In Robert Mountford's transition from the terrifying Prospero to the comical Trinculo, we are permitted a glimpse beyond the terrorizing desire for vengeance and into the relations between the powerful and powerless. We are permitted comic relief in what is often a very intense production, and we glimpse the possibility for redemption and humor beyond Prospero's austerity. In other pairings—Chris Jack as Ferdinand and Sebastian, Jessica Manley as Miranda and Alonso, and Keith Thorne as Caliban and Gonzalo—the doubling takes on even greater cultural and political significance. The boundaries between good and evil, oppressor and oppressed, are blurred as the actors switch from one character to another. The slave figure of Caliban is revealed also to be a great and loyal advisor, reminding the audience of the days when Caliban was treated as Prospero's guide to the island and even as a surrogate son. Our conception of Prospero's daughter, hidden away behind the Muslim veil for most of the production, is also subverted as the veil is removed to reveal the figure of highest political authority on the island, King Alonso. Even as we are asked to draw cultural conclusions based on the behavior or dress of the characters, those assumptions and conclusions are fundamentally challenged by the versatility of Tara's actors and the insistence on multiple identities.

Prospero and Miranda. Photographed to accompany

a review by Dominic

Cavendish

in The Telegraph.

|

There are, however, also problems with Verma's casting decisions, which leave the production open to the anxieties of the mainstream white English Shakespearean audience. Even in Jessica Manley's transformation into King Alonso and Keith Thorne's movement into the character of Gonzalo, the political authority still lies with a white "man" (even if acted by a woman) who uses the loyal African as his guide and advisor. This relationship is further complicated by the fact that the only two women cast in the production—Jessica Manley and Caroline Kilpatrick—are conspicuously white compared to the ethnically diverse male cast members. Ariel in particular, dressed in a white smock and lit by the spotlight, almost glows in her paleness. It is hard not to see her blinding whiteness as the Anglo-English conception of the angelic—a beatified, Disneyesque Tinkerbell—and, likewise, it is difficult not to see a correlation between Prospero's violent protection of his daughter's purity and virginity and her status as a white woman in an ethnically diverse world. In placing a white woman under the veil and putting her fate in the hands of Prospero, the all-powerful father who conjures a marriage for her, Verma draws upon all manner of anxieties about the position of women in Muslim culture and more ancient fears about the safety and purity of white women in the hands of black men.

This concern is made even more explicit in Keith Thorne's portrayal of Caliban, visually the darkest member of the cast. Thorne's Caliban is a child, hysterically funny in his interactions with Trinculo and Stephano for his infantile insistence upon their divinity as they blatantly abuse him. This Caliban may have taught his master how to navigate the island, but the idea that he could have been heir to Prospero's magic is laughable. And, as Loxton writes in his review, Caliban's "attempted rape of Miranda must have been some kind of boyish blunder." The alleged rape, however, is significantly and profoundly ambiguous since Caliban simultaneously—and paradoxically—represents the threat of the savage black man to the innocent white woman, as well as the infantilism and incompetence of the native. In both cases, Verma's production does more to reinforce, or at least bring to light, racial stereotypes and anxieties than to subvert them.

Nonetheless, even in drawing on racial fears and anxieties, Tara's production of The Tempest is at once a commentary on the contemporary world of its specific performance and a valuable contribution to the body of Shakespearean productions. Seen in light of the performances and adaptations that precede it, the cultural work being done here is profoundly new and provocative. Audiences anticipating traditional Shakespeare and even audiences expecting the conventional postcolonial interpretation of The Tempest are challenged. In an increasingly globalized world, one in which the threat of Western European domination is paired with the simultaneous threat of Islamic fundamentalism, Tara's production attempts to link the motifs of power that are common to both. An African man enslaved by a fanatical Muslim leader played upon a stage in imperial London forces upon its audience a recognition of contemporary global relations of power and domination. What the doubling means for the end of the production is that the audience is denied a full scene of reconciliation and absolution, since it is physically impossible to gather all characters of the Shakespearean cast on-stage at once. Thus, the same theatrical device that permits us to see the cracks and links between identities is the same device that prohibits us from leaving the theatre with a fully reconciled and resolved picture of these racial, religious, and cultural tensions. Verma challenges his audience to see that relationships of power and subjugation cannot be simplified into the relationship between "East and West". The price of this insight is the revelation that we have not yet reached the moment of full absolution.

* This essay is adapted from BAKER, EVANS, MONAGHAN-PISANO, NAM, WILLIAMS, 2008. Review of Shakespeare's The Tempest (directed by Jatinder Verma for Tara Arts) at the Arts Theatre, London, January 2008. Shakespeare 4(3), 320-323.

- [1] CBS NEWS, 2008. Bishop: Parts of UK 'No-Go' Due to Radical Islam. CBS News. [1st April 2008].

- [2] LOXTON, HOWARD, 2007. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Tara Arts Studio, London. The British Theatre Guide. [21st February 2008].

- [3] CAVENDISH, DOMINIC, 2008. On the Road reviews: The Tempest and The Woman Hater. The Daily Telegraph. [21st February 2008].

- [4] VERMA, JATINDER, 2008. What the Migrant Saw. The Guardian. [21st February 2008].

- [5] MASSAI, SONIA, 2005. Defining Local Shakespeares. In: MASSAI, S., ed., World-Wide Shakespeares: Local appropriations in film and performance. Oxford: Routledge, 4.

- [6] FISHER, PHILIP, 2008. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Arts Theatre London. British Theatre Guide. [21st February 2008].

- [7] KAHN, COPPÉLIA, 2001. Remembering Shakespeare Imperially: The 1916 Tercentenary. Shakespeare Quarterly 52(4), 461

- [8] See the following critics: FISHER, CAVENDISH, LOXTON, and BILLINGTON.

- [9] FISHER, 2008.

- [10] KUMAR, 2003, 186.

Sources Consulted

- BHABHA, HOMI, 1994. The Location of Culture. London & New York: Routledge.

- BILLINGTON, MICHAEL, 2008. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Arts Theatre, London [online 21 February 2008].

- CADBURY, HELEN, 2007. William Shakespeare's The Tempest: Education Resource Pack . Tara Arts. [online 21 February 2008].

- CAVENDISH, DOMINIC, 2008. On the Road Reviews: The Tempest and The Woman Hater. The Daily Telegraph. [online 21 February 2008].

- CBS NEWS, 2008. Bishop: Parts of UK 'No-Go' Due to Radical Islam. CBS News. [online 1 April 2008].

- EASTHOPE, ANTONY, 1999. Englishness and National Culture. London: Routledge.

- FISHER, PHILIP, 2008. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Arts Theatre, London. British Theatre Guide. [online 21 February 2008].

- GIKANDI, SIMON, 1996. Maps of Englishness: Writing Identity in the Culture of Colonialism. New York: Columbia University Press.

- HADFIELD, ANDREW, 2004. Introduction: English Literature and Anglicized Britain. In: HADFIELD, A., Shakespeare, Spenser, and the Matter of Britain. New York: Palgrave Macmilan.

- HEMMING, SARAH, 2008. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Rose Theatre, Kingston. The Financial Times. [online 1 April 2008].

- KAHN, COPPÉLIA, 2001. Remembering Shakespeare Imperially: The 1916 Tercentenary. Shakespeare Quarterly 52(4).

- KUMAR, KRISHAN, 2003. The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- LOXTON, HOWARD, 2007. The Tempest by Tara Arts, Performed at the Tara Arts Studio, London. The British Theatre Guide. [online 21 February 2008].

- MASSAI, SONIA, 2005. Defining Local Shakespeares. In: MASSAI, S., ed., World-Wide Shakespeares: Local appropriations in film and performance. Oxford: Routledge.

- VERMA, JATINDER, 2007. Towards Cultural Literacy: Speech made marking Tara's 30th Anniversary, 11 June 2007. London: Arts Theatre.

- ---, 2008. What the Migrant Saw. The Guardian. [online 21 February 2008]

- ZABUS, CHANTAL, 2002. Tempests After Shakespeare. New York: Palgrave.

|