| “When we perform, people often ask us, what's changed because of these performances?” asks Sudhanva Deshpande before the performance of Tathagat, the latest play at Jana Natya Manch. Indeed, what's the point of it? A couple of actors assemble a crowd, a play begins, a play ends, the crowd disperses, so do the actors. They come to another place, the ritual is repeated. Yet, ask any actor what the point is of doing the same play over and over again, and she will say: each performance was different. It is the same play, but the performances are not. This difference is the point of it all.

Deshpande's question had a pragmatic aspect as well. Jana Natya Manch, known as Janam, is not just any theatre troupe—it is regarded as one of India's premier political theatre groups. Thus the question Deshpande quoted probably was, “What is changed politically by all these years of theatre performances?” In other words, has there been any real, political change at all? It's a wrong-headed question to ask, for it ignores an equally important word in the phrase “political theatre”: theatre. To that end, the question be reformulated once more: Can any theatre affect any change at all? Any change it can possibly affect, whether political or not, must be within the theatre itself. Janam is a living testament to this phenomenon of change within the theatre.

So why does Janam self-fashion itself as a political theatre group? This question brings us back to 1973 [1], the year of Janam's formation. Safdar Hashmi (1954-1989), whose name is synonymous with the phrase “Indian political theatre,” was one of the founders and principle movers of the organisation. His central role in those early years gives many the impression that he was the figure around which the group existed. This is a misconception. Hashmi did do a majority of the writing of the early plays, but he was not the sole playwright, and he was not among the many playwright-director-managers of theatre companies in independent India.

Another frequent misconception about Janam is that it is exclusively a street theatre group. (This has resulted in some misconceptions about political theatre in India in general: sometimes street theatre is used synonymously with political theatre). Hashmi, writing on the occasion of completing a decade of work, writes:

In our view, it is absurd to speak of a contradiction between proscenium and street theatres. Both belong equally to the people. Yet, there is certainly a contradiction between the proscenium theatre which has been appropriated by the escapists, the anarchists and the revivalists, and the street theatre which stands with the people; just as there is a contradiction between reactionary proscenium theatre and progressive proscenium theatre, or between democratic street theatre and reformist and sakari [governmental] street theatre.

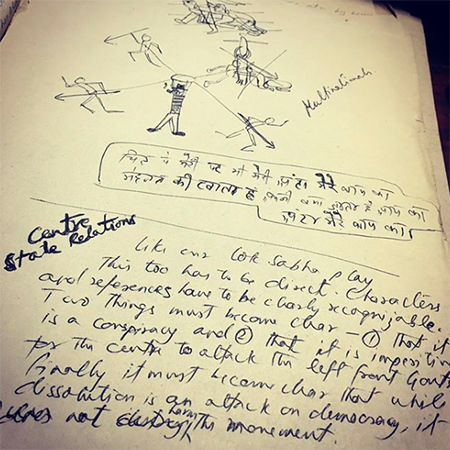

A page of Safdar Hashmi's notes on a play in development. // source |

The frequent use of the term “people” gives us the next clue about Janam: its association with the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

The Communist Party of India (CPI) was not the only anti-imperialist party in India, but it was the most organised of the lot. After Independence, a group within the CPI believed they must work alongside the main nationalist party, the Congress. This faction was the more influential one within the Party and aligning with the Congress became the official Party line. Tensions remained, however, and, in 1964, the Party split, with an offshoot forming the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPIM.

Hashmi, along with Janam, was with the CPIM. This history is important because Janam constantly worked along with the trade unions and other mass organisations of the CPIM to perform their plays in front of audiences who would have never visited the proscenium theatres. And these audiences would number in thousands. Janam's early experiments with space and dramaturgy would be pragmatic experiments, but from that pragmatism would come a form of theatre that was neither the proscenium (and, to use Hashmi's term, bourgeois) theatre nor the pre-modern, folk performances. Political ideology aided the aesthetic that this theatre aimed for, connecting them with audiences that previous forms of theatre could never get. In turn, those audiences, mostly comprising the working class, gave them new stories to tell in newer ways.

On 1 January 1989, after almost two decades of this work, Janam was attacked during a performance of the play Halla Bol by goons hired by the Congress Party. Hashmi and another worker succumbed to their injuries the next day. Janam returned to the same place the next day and finished the play. Every year since then, Janam returns to Jhandapur to the same spot and performs a new play. The program is jointly organised by Janam and the Centre of Indian Trade Unions: another example where the group teams up with a union organization to perform.

I visited one such event in 2017 when I was producing and directing a news feature [2]. The energy among the crowd at the B.R. Ambedkar ground in Jhandapur is infectious every first of January; with grandparents holding the hands of their grandchildren, and sweetmeats, trinkets, and papads on offer at the gate, the scene resembles a mela or fair. But what changes this congregation from a mere celebration to a politicisation are the plays and the speeches of the political leaders. It doesn't mean everyone comes out of the gathering a leftist—and thank god they don't, because political work is hard and a long, drawn-out process. Rather, everyone becomes a little more aware of the reality around them. After my 2017 visit, for instance, I was left wondering if Subhashini Ali's speech against the disastrous demonetisation policy of the current right-wing government might have been as good a performance as the plays…

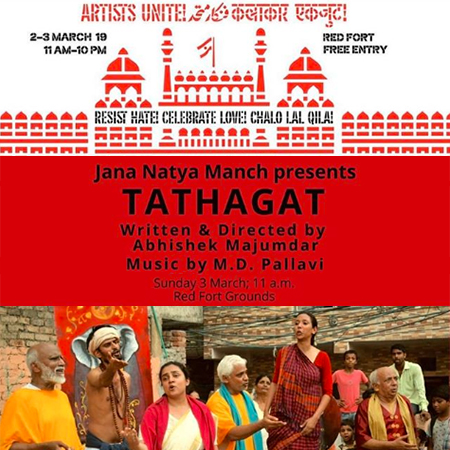

Flyer for a performance of two of Janam's classic plays at the Artists Unite! festival in March 2019. // source |

Janam is not just a political theatre group—they're a political theatre group who are extremely stubborn. The annual January first event is a testament to this. Come what may, they'll continue their practice. Not only will they perform a day after Hashmi gets killed, they will do it every year. And it is important to understand that while the events of 1989 are at the heart of Janam's story, they remain an active stubborn political theatre group. Their recent productions have included Hamesha Samidha, a play jointly produced by Freedom Theatre of Palestine—whose founder, Juliano Mer Khamis, was also killed, in 2011. Another recent show is Tathagat. Now, Janam hasn't done a stage production in quite a few years, but Tathagat , written and directed by Abhishek Majumdar, is a daring experiment for the street theatre form, precisely because it borrows so much from the conventions of the proscenium stage. Unlike a lot of street plays which are parables working with stock characters, Tathagat is a historical play, and one that makes a better comment on the present than any play set in contemporary times could.

Alain Badiou, in Rhapsody for the Theatre , says that the theatre has spectators, whereas cinema has viewers. He writes:

. . . if cinema is everywhere, it is no doubt because it requires no spectator, only the walls surrounding a viewing public. Let's say that a spectator is real, whereas a viewing public is merely a reality, the lack of which is as full as a full house, since it is only a matter of counting. Cinema counts the viewers, whereas theatre counts on the spectator, and it is in the absence of either one or the other that critics, in a disastrous paradox, invent the spectator of a film and the viewer of a play. [3]

I saw Tathagat in September last year. When the play ended, I got an answer to the question “What has changed?” I was wondering if the characters in the play were in some far-away land from the past, or if they're in the present. This is what had changed: it made me think. This is the wager of Janam, indeed the wager of all theatre: the thinking spectator. Janam has been creating such spectators for four decades.

The photos above are excerpted from the Instagram account of Sudhanva Deshpande, an actor and publisher, and one of the creative directors of Janam. His book about Safdar Hashmi will be published in January 2020.

Notes

- According to Arjun Ghosh, author of A History of the Jana Natya Manch , who dates it to 1973; but Safdar Hashmi cites October 1979 as the founding moment. // return

- "Remembering Safdar Hashmi (12 April 1954 – 2 January 1989)." An ICF Report from Jhandapur. Indian Cultural Forum, accessed November 3, 2019. // return

- Badiou, Alain. Rhapsody for the Theatre. Edited and introduced by Bruno Bosteel; translated by Bruno Bosteels with the assistance of Martin Puchner. London: Verso. 2013. Pg 2. // return

See also...

|