|

It was famously Walter Pater who, in 'The School of Giorgione' chapter of The Renaissance, told us that all art continually aspires towards the condition of music. Pater begins that chapter by distinguishing between the arts, saying:

It is the mistake of much popular criticism to regard poetry, music, and Painting — all the various products of art

- as but translations into different languages of one and the same fixed quantity of imaginative thought.

... and going on to qualify this as follows:

although each art has thus its own specific order of impressions, and an untranslatable charm, while a just apprehension of the ultimate differences of the arts is the beginning of aesthetic criticism; yet it is noticeable that, in its special mode of handling its given material, each art may be observed to pass into the condition of some other art, by what German critics term an Anders-streben-a partial alienation from its own limitations, by which the arts are able, not indeed to supply the place of each other, but reciprocally to lend each other new forces.

It is from here that he proceeds to the famous sentence:

All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music. For while in all other works of art it is possible to distinguish the matter from the form, and the understanding can always make this distinction, yet it is the constant effort of art to obliterate it. That the mere matter of a poem, for instance — its subject, its given incidents or situation; that the mere matter of a picture — the actual circumstances of an event, the actual topography of a landscape — should be nothing without the form, the spirit, of the handling; that this form, this mode of handling, should become an end in itself, should penetrate every part of the matter: — this is what all art constantly strives after, and achieves in different degrees.

And this is true in the sense that we don't expect music generally to invite differentiation between matter and form, or to imitate life too closely, whereas imitation was the very stuff of visual art and literature.

In the Renaissance that Pater is discussing verisimilitude was a kind of necessary qualification for greatness. Giorgio Vasari, author of The Lives of The Artists, who is not to be trusted in all factual matters but is a good guide to taste and expectation, tells in his life of Giotto how the great proto-Renaissance artist Cimabue

going one day on some business of his own from Florence to Vespignano, found Giotto, while his sheep were browsing, portraying a sheep from nature on a flat and polished slab, with a stone slightly pointed, without having learnt any method of doing this from others, but only from nature; whence Cimabue, standing fast all in a marvel, asked him if he wished to go to live with him.

The pinnacle of Giotto's imitative art according to Vasari is best demonstrated through this anecdote:

It is said that Giotto, while working in his boyhood under Cimabue, once painted a fly on the nose of a figure that Cimabue himself had made, so true to nature that his master, returning to continue the work, set himself more than once to drive it away with his hand, thinking that it was real, before he perceived his mistake.

In other words the value of a work in this case is partly dependent on it seeming to be something else, not the work. The paint reaches maximum power by not seeming to be paint but something else: a natural object. One should be fair to Vasari and allow that he did not base his valuation of Giotto entirely on the way he painted realistic flies.

Nor would we think, looking at Giotto's marvelous work — Giotto being one of the greatest of painters, in my opinion — that his grasp of photorealism was particularly convincing. It is not what we go to him for. We go to him for a new understanding of religious drama and of the human part in it, so the religious and the divine become comprehensible in human terms.

Vasari understands this of course, but the sheer technical possibility of painting the way Giotto painted is not beside the point to him. It is bringing alive, the way the fly is alive, that is, for Vasari, a central concern of art.

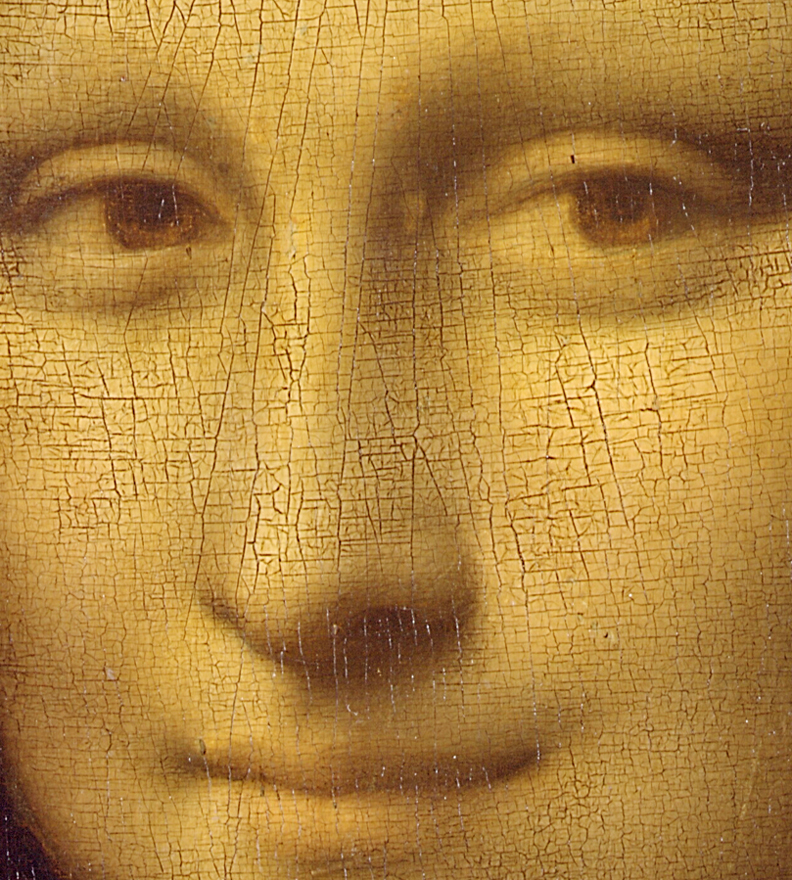

When Vasari comes to discuss Leonardo da Vinci, he once again concentrates on the impression of life. Here he is on the Mona Lisa in Volume 4 of the Lives:

The eyebrows, through his having shown the manner in which the hairs spring from the flesh, here more close and here more scanty, and curve according to the pores of the skin, could not be more natural. The nose, with its beautiful nostrils, rosy and tender, appeared to be alive. The mouth, with its opening, and with its ends united by the red of the lips to the flesh-tints of the face, seemed, in truth, to be not colours but flesh. In the pit of the throat, if one gazed upon it intently, could be seen the beating of the pulse.

Let us now return to Pater and his understanding of the same painting.

|